Property ownership can seem straightforward, but in reality, it carries complex implications that can ripple beyond your lifetime. How you decide to title your assets - whether sole, joint, or more intricate - shapes how they transfer, impacts whether your loved ones face legal hurdles, and determines how much of your wealth they ultimately inherit. These choices directly affect your legacy, making it crucial to plan intentionally.

In today’s post, I’d like to dive into the different types of property ownership interests and how understanding these distinctions can be a game-changer for your estate planning decisions.

Legal vs. Equitable Ownership

Before exploring specific ownership types, let’s clarify two critical terms: legal ownership and equitable ownership. These represent different facets of property rights, both essential in estate planning and asset protection.

Legal ownership is the official title on record. It gives you the authority to manage, sell, or transfer the property. However, legal title alone doesn’t guarantee control over the benefits of the property.

Equitable ownership, on the other hand, is the right to benefit from the property’s value, income, or other advantages, even if you don’t hold the title. For instance, in some types of arrangements, one person may hold the legal title, while another person, an equitable owner, enjoys income or use of the property.

Now, let’s take a closer look at how these interests are reflected in different types of ownership.

Sole Ownership

Sole ownership, also called fee simple, is the simplest form of property ownership, giving one person complete control and rights over the asset. This means you can use, sell, gift, or leave the property as you choose. For example, if you own a savings account, car, or home solely in your name, you have full control. However, there’s a downside: when you pass away, the full value of these assets is included in your gross estate, and they must go through probate. This process can add delays, costs, and stress to your heirs.

Additionally, assets owned solely lack creditor protection, so creditors can claim them to settle any outstanding debts.

Imagine you own a family cabin. While sole ownership is simple in life, if you pass away, the cabin will need to go through probate before your children can fully inherit it - either according to your will or, if there’s no will, through the state’s intestacy laws. This could result in months or even years of delays before they can take ownership. So, although sole ownership keeps things simple during your lifetime, it may create complications for your heirs down the line.

Tenancy in Common

Next is Tenancy in Common, the most common and flexible form of joint ownership often used among family or business partners. In this arrangement, two or more people each hold an undivided percentage share in a property, typically based on their contribution to the property’s purchase price.

If the ownership shares don’t match each person’s contribution percentage, it may be considered a gift.

For instance, Joyce and James bought a property for $100,000, with Joyce contributing $70,000 and James $30,000. They agreed to hold the property as tenants in common, each with a 50% share. In this case, Joyce effectively made a $20,000 gift to James.

Each owner can sell or bequeath their share independently. When one owner passes, their share doesn’t automatically transfer to co-owners but instead goes through probate, following their will or state intestacy laws. The deceased owner’s share is included in their estate based on fair market value. A key benefit of tenancy in common is that each co-owner’s debts affect only their portion of the property, so creditors can only claim that specific share.

Imagine you and a sibling co-own a $300,000 beach house as Tenants in Common, each with a 50% share. If your sibling defaults on a loan, creditors can only claim their half. Upon one’s passing, each share can be left to family members rather than to the sibling.

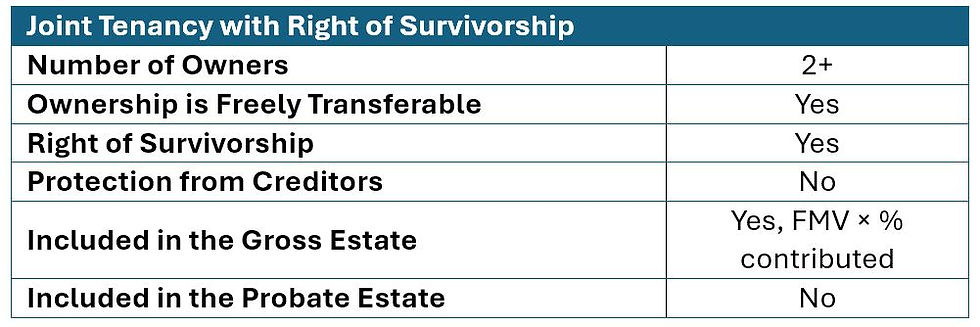

Joint Tenancy with Right of Survivorship

Joint Tenancy with Right of Survivorship (JWTROS) is often chosen by spouses or close family members seeking simplicity. Here, each co-owner holds an equal share. Since there is automatic right of survivorship, upon one’s death, their share automatically transfers to the surviving owners, bypassing probate. This type of ownership allows for smooth transfers but requires all parties to agree on the property’s future, which isn’t always the case. The good news is that any joint tenant can sever their interest in the property without needing consent from the others.

Estate tax considerations for JTWROS include the “actual contribution rule” - only the decedent’s share (based on their original contribution) is included in their estate. For spouses, each is deemed to have contributed 50%, regardless of actual contribution.

For example, if you and your spouse own a home as joint tenants, upon your passing, your spouse inherits the entire property without probate. However, if you co-own with a child who didn’t contribute to the purchase and you gifted them 50% of the property’s value, then, under contribution rules, the full property value would be included in your estate.

As for creditor protection, JTWROS offers limited shielding since a creditor can pursue a debtor’s share if that owner has unpaid obligations. Upon that owner’s passing, the creditor may lose the claim on that share if it passes to the surviving co-owner.

Tenancy by the Entirety

Exclusive to married couples in certain states, Tenancy by the Entirety is similar to JTWROS but with added protections. Neither spouse can transfer their interest without the other’s consent. This condition prevents either spouse from ending the other’s right of survivorship by transferring the property to a third party. When one spouse passes, ownership automatically transfers to the surviving spouse without probate. For estate purposes, only the decedent’s half is included, similar to JTWROS

This structure also shields the property from individual creditors, protecting it from debt claims against one spouse. In other words, if one spouse has debts, creditors can’t come after the property unless both spouses are liable. When the marriage ends, Tenancy by the Entirety typically converts to Tenancy in Common, which changes who inherits what.

Community Property

In states like Arizona, California, Idaho, Louisiana, Nevada, New Mexico, Texas, Washington, and Wisconsin, Community Property is the default for married couples. Any property acquired during the marriage is equally owned by both spouses. Property acquired before marriage, or received as a gift or inheritance during marriage, remains separate. However, if separate property is mixed with community property, it’s often treated as community property.

Community property offers unique tax advantages: when one spouse passes, the survivor receives a full step-up in basis, potentially reducing future capital gains taxes. However, in some states, the deceased spouse’s 50% share may go through probate if there’s no automatic right of survivorship.

For example, imagine a California couple buying a rental property. Upon one’s death, the other receives a full step-up in basis, saving potentially significant capital gains taxes when sold.

In terms of estate tax, each spouse’s 50% share is included in their estate. As for creditor protection, Community Property doesn’t offer any, so debts owed by one spouse can affect both. However, if you move from a community property state to a common law state, you can separate community property by gifting it to your spouse, utilizing the unlimited marital deduction to avoid gift taxes. Conversely, if you relocate from a common law state to a community property state, property acquired before the move generally retains its separate status.

Other Special Property Ownership Forms

Beyond the common types, there are special property ownership forms that may be useful depending on your estate planning needs. For instance, split ownership divides property interests based on a specific event or time period. When the event occurs, the first owner’s interest ends, and the next owner’s begins. This creates a present interest for the current beneficiary and a future interest (or aka remainder) for the waiting owner. If the original owner holds the future interest, it’s called a reversionary interest.

Life Estate

For example, a Life Estate arrangement gives someone the right to use a property or the right to the income for their lifetime, but ownership itself doesn’t transfer. This is a great option if you want someone - like a surviving spouse- to continue living in the family home without actually transferring the title. When the life tenant passes, the property automatically moves on to a designated remainder beneficiary, skipping probate.

From an estate perspective, life estates are usually excluded from the life tenant’s taxable estate since they lack disposition powers. Life estates may offer some creditor protection, though this varies. The life tenant’s interest can be claimed by creditors during their lifetime, but upon their passing, the property transfers to the remainderman, typically free from the life tenant’s creditors. However, the remainderman’s interest may be subject to their own creditors' claims.

To give you an example, imagine leaving your home to your spouse through a Life Estate. They can live there as long as they wish, but once they pass, the home goes to your children. This way, your spouse is taken care of, and your children inherit the property smoothly, without probate or additional steps.

Term Interest

A Term Interest allows someone to live in or use a property for a set period, rather than their lifetime. This can be helpful when you want to offer temporary support without giving away permanent ownership. After the term ends, the property reverts to a designated heir.

Let’s say you want your grandchild to use a home in Florida for five years while they get back on their feet. In your will, you would leave that family member an interest to stay at the home temporarily, no longer than 5 years. Once the period is up, the property transfers to your heirs.

Final Thoughts on How to Title Assets

As you can see, understanding property interests goes beyond just “who owns what.” It’s about protecting your assets, planning for the future, and making sure your loved ones avoid legal and financial headaches. Each type of property ownership offers unique benefits and potential pitfalls depending on your goals, life stage, and family situation. Taking the time to understand these now and make potential changes to the ownership structure of your assets, can save everyone from future complications, ensure your assets are protected, and let you build a legacy that reflects your wishes.

If you're looking to review your estate planning strategy or for tax-efficient strategies to transfer your wealth to heirs and charities, feel free to book an Estate Clarity meeting with us.

Commentaires